Author: João Victor Stuart

GHRD Coordinator: International Justice and Human Rights team

LLB Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

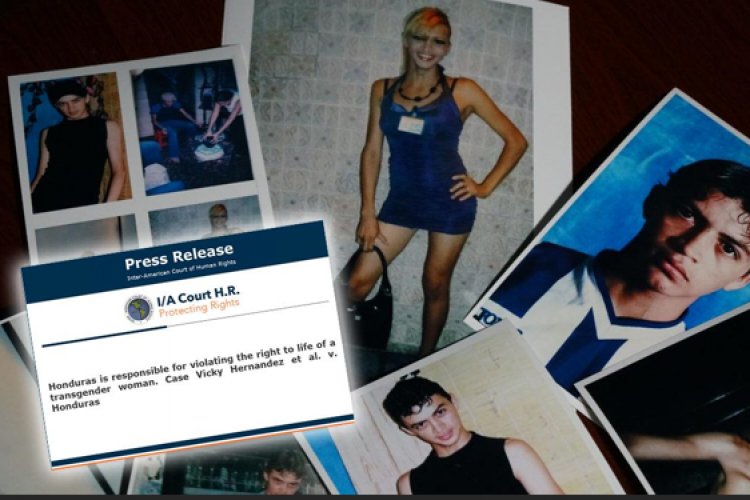

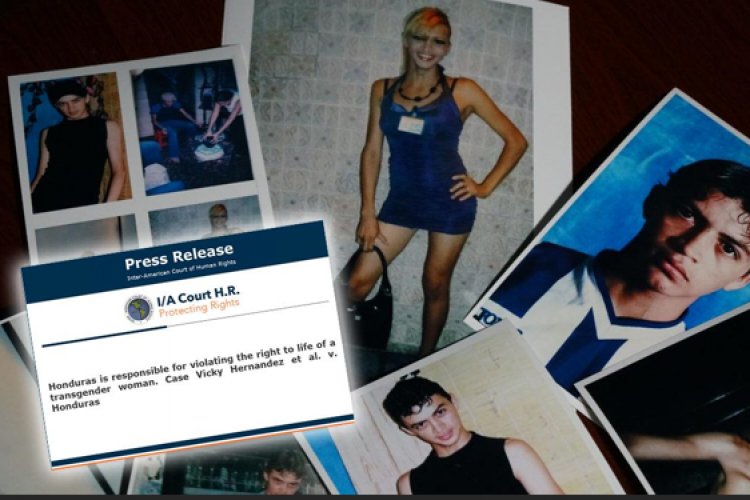

Vicky Hernandez ET Al v. Honduras

Author: João Victor Stuart

GHRD Coordinator: International Justice and Human Rights team

LLB Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Comments